More hunger, less fat burned

Results showed that hunger pangs doubled for those on a night-eating regime. People who ate later in the day also reported a desire for starchy and salty foods, meat and, to a lesser extent, a desire for dairy foods and vegetables. Senior author Frank Scheer, director of the Medical Chronobiology Program in the Brigham’s Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders.

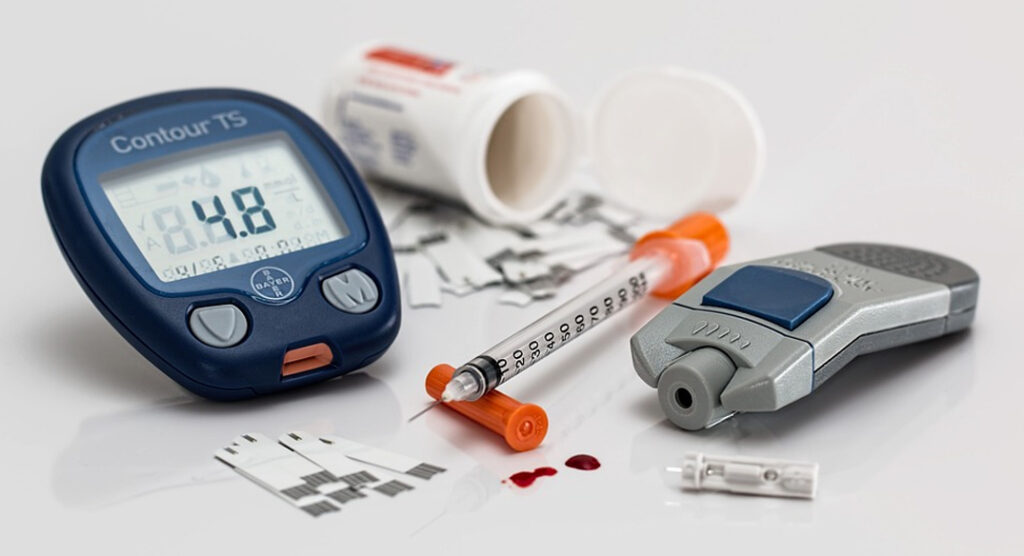

By looking at the results of blood tests, researchers were able to see why: Levels of leptin, a hormone which tells us when we feel full, were decreased for late eaters versus early eaters. In comparison, levels of the hormone ghrelin, which spikes our appetite, rose.

“What is new is that our results show that late eating causes an increase in the ratio of ghrelin and leptin averaged across the full 24-hour sleep/wake cycle,” Scheer said. In fact, the study found that the ratio of ghrelin to leptin rose by 34% when meals were eaten later in the day.

“These changes in appetite-regulating hormones fits well with the increase in hunger and appetite with late eating,” Scheer said.

When participants ate later in the day they also burned calories at a slower rate than when they ate at earlier times. Tests of their body fat found changes in genes that would impact how fat is burned or stored, the study found.

“These changes in gene expression would support the growth of fat tissue by formation of more fat cells, as well as by increased fat storage,” Scheer said.

It’s not known if these effects would continue over time, or on people who currently take medications for chronic disease, which were excluded from this study. Further study is needed, the authors said.

source : edition.cnn.com